|

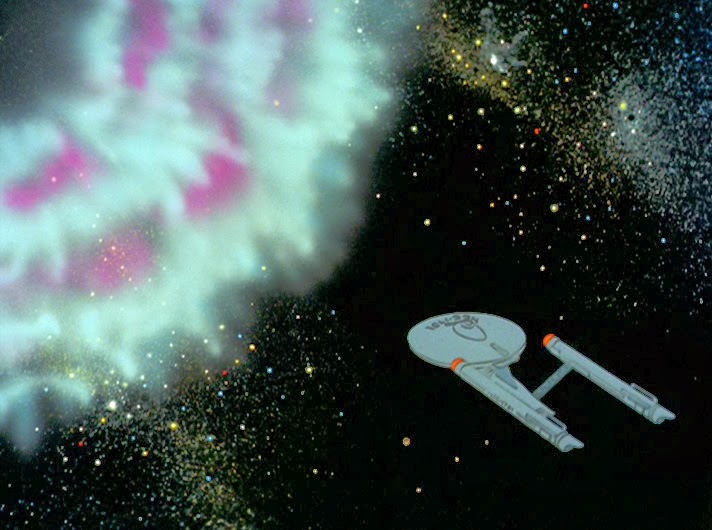

| "Turning back time, Fred Bronson recalls his service to Starfleet." |

“We're all dead men walking, Agent, and it doesn't please me any more than it does you. Look in a mirror sometime if you don't believe me. I have. Nevertheless, you are more correct then you think. Everywhere is here and now in a Time War. This brutal fighting will come to an end, just not on your terms. No matter which way our gamble plays off, we still want to go forward. You'd take the entire galaxy backwards as you retreat into your own obsolescence. We will prevail. And when we do, it will be the most terrible calamity this galaxy has ever seen. Of that I am as certain as it is possible for a person to be about anything, because I've already foreseen it come to pass. This battle was only the beginning.”

“If your soldiers die, they will die for nothing. We're not going to let you commit suicide. Whether they die or not, you'll still stand trial for your crimes against the timeline. Your war is over. This ends here and now.”

“And when is that ever the case with time travel? You're making a pointless argument. The actions I take in service of my cause may later be determined to be just and they may not, but right now I'm doing what my instinct tells me is right, and I'm convinced this cause is a righteous one. I'm not too keen on the part fate has given me, but it's my role to play and I'll give the best performance I can. None of us are destined to come out the other side of this war alive, Agent. That much I know.”

“And yet you would take the lives of countless people into your hands, depriving them of their agency as you singlehandedly rewrite centuries of history! Your actions are not in keeping with the ideals you espouse.”

“This isn't about ensuring the future will be better for us personally, not entirely. It's about giving everyone a second chance. A second life. A good life under a despotic Empire is neither truly good, nor truly living, no matter how much enlightenment rhetoric the Imperial Overlords happen to use. You used to feel the same way. I know, I've seen it.”

“And, naturally, you of course have the best vision of the future...”

“At least we acknowledge we *can* change. We believe a utopia that doesn't allow for people to learn and grow is no utopia, especially if it means obligatory subservience.”

“It's childish to go back and try to change your mistakes instead of learning from them.”

“It's only self-interest inasmuch as it's an interest shared with a large portion of the affected multiverse.”

“Regardless of the size and scope of your particular outfit, your crimes are the most severe. So far, you've succeeded in ways many others haven't come close to. History has been significantly altered as a direct result of your actions, perhaps irreparably so. You wish to change history to serve your own interest. That alone means the Cabal is without question the most dangerous combatant in this fight.”

“The Cabal is a haphazardly organised group of mercenaries armed with the temporal equivalent of sticks fighting the entire Imperial Armed Space Forces. Not that we aren't efficient and competent in our own way, I'm quite proud of what my people have been able to accomplish so far, but the metaphor still fits. Now, you may have absorbed and internalized your own propaganda, but, in case you've forgotten, there are other factions in this war aside from us. Some of those are actual military outfits, and have considerably more nefarious aims than securing liberty and dignity. Have you ever considered using some of your resources to combat them, or are you too fixated on the scary outsiders who don't play by your rulebook?”

“All I see right now is a known fugitive making a desperate plea for clemency. You're running a terrorist organisation motivated purely by hatred and selfishness, and for that I will see all of you brought to justice.”

“Because I can see ahead, and you should be able to as well. Or perhaps you can, but you don't mind what you see. What you would condemn the galaxy to. A future living under the boot of a homogenous, monolithic conquering force growing and expanding in perpetuity until the entire universe is choked out. I can't decide what would be worse: That you can't see, or that you won't see.”

“You play the romantic and heroic outlaw, but what makes you any different? Upholding this corrupted timeline would benefit your aims as much as you claim correcting it would benefit ours.”

“You're even more hopeless and naive then I thought you were if you believe that.”

“That's where you're so misguided! Laws exist for a reason! They're created so that everyone has an equal opportunity for success and is guaranteed a measure of dignity! Without some structure, without some order, we would all be helpless and in a state of perpetual danger! We as a community, as a collective, have created a perfect utopia here. There is no want. There is no suffering. Each and every person is equal. To act in defiance of that is to act in defiance of peace and prosperity!”

“And what, aside from your frankly obscene amounts of power and authority, gives you the right to say that? You obviously haven't come to those conclusions based on a commitment to reduce suffering and maximize dignity otherwise you'd be on my side.”

“It 'doesn't suit' me because it's a corrupt timeline! This is not the way history is meant to play out! You would put the stability of the entire time-space continuum in peril!”

“It would seem we have two wildly different conceptions of self-interest, Agent. From my perspective, the lives of the millions of people on those planets, not to mention the hundreds aboard that ship and the countless other people affected by this act, mean considerably more than temporal law, which in this case will have you erasing two entire years of galactic history, largely because it doesn't suit you.”

“You violated commonly accepted temporal law for your own reasons of self-interest.”

“I would have thought someone of your considerable age and experience would be able to recognise that facts are mutable, situational things in the best of circumstances. And these are hardly the best of circumstances.”

“The Cabal broke the Accords and initiated open hostilities, and no matter how much you try to change the subject or diffuse blame that remains a fact. I was present when the opening salvo was fired and I have documented evidence to support my argument! Please don't waste your breath and our time, it shall accomplish nothing and only delay the inevitable.”

“Peace achieved through stomping out and silencing out any dissenting voices, you mean. Or did you momentarily forget you currently have me staring down an Imperial Armada the size of a solar system that spans at least three discrete timelines? Funny how you don't seem to grasp the irony of that.”

“You don't speak for the oppressed. You're just a megalomaniacal manipulator with delusions of godhood who's gotten far too good at using people to satisfy your own self-centered interests. And even if you did, you'd be mistaken. We strive only for peace with people throughout space and time. It is you who seek out conflict.”

“No, Agent. You started it. Or, to be precise, you will start it. Figure it out. You have temporal observatories, don't you? And I know the Guardian of Forever exists in your timeline-I believe we've had that little discussion already. Well...We have from my perspective at least. All we're doing is fighting back and reclaiming our personhood. Oppressed people tend to do that. And you should've expected that.”

“I know it's about you and your little faction flagrantly and deliberately violating the Temporal Accords, potentially endangering every civilized race in the galaxy. Let's remember it's your kind who started this whole war.”

“You still don't understand what this is all about, do you? You really don't! But I suppose we should've expected it.”

“I don't have time for your speechifying, and your appropriation of other people's words fail to make you sound the slightest bit more intelligent. You're surrounded, outmanned and outgunned. This war is over. Please. For the sake of yourself and your people, not to mention the countless lives lost in this senseless slaughter, please surrender. Your crew will be treated with the utmost respect while they're being processed”.

“'History is written by the victors'. And 'to the victor goes the spoils'. Isn't that what they used to say?”

There is a brilliant flash of light, a “winking out” and then everything goes dark.

End.